- Home

- Robert Lowndes

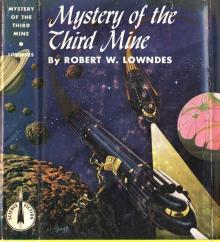

Mystery of the Third Mine

Mystery of the Third Mine Read online

Mystery of the Third Mine

A Science Fiction Novel

By ROBERT W. LOWNDES

Jacket Designed by Kenneth Fagg

THE JOHN C. WINSTON COMPANY

Copyright, 1953 By Robert W. Lowndes

FIRST EDITION

To my wife, Dot, who wanted me to write a book; and to Scott, Lester, and Sal, who made it possible

Mining on Ceres

When we try to picture the way in which human beings may live on other planets in the future, there are three main sources for our background. Our picture of the planets themselves comes from what science has learned of them after centuries of studying the sky. In some cases there is not very much to go on; in others we have learned a great deal. We can be reasonably sure about such matters as gravity, atmosphere, general climate, and about how much light there would be on some of the planets. From there on, we try to sketch in a more nearly complete picture.

Our ideas of how man may reach another planet come from present-day development in rockets. There are countless details that have been established or suggested by years of making tests. We know what has been done, and can imagine what may be only one or two steps beyond. After this, we try to figure out what will be needed and what seems to be the most likely way to fulfil those needs. It’s the same system used in picturing how people may solve the problem of keeping alive and healthy once we arrive safely on another world.

As soon as you have a group of people living together, pretty well cut off from everyone else, then a society begins to take form. This is where history comes in. You’ve heard the old saying, "History repeats itself.” That is partly true. It’s a useful saying if you remember that it does not mean, “The same things keep on happening over and over." We couldn’t make any sense at all out of what we learn about people who lived hundreds, or thousands, of years ago, if they were completely different from us. But if they were exactly the same, we wouldn’t have to study history, either. We’d know that the past was just like the present.

So our picture of a future society on another planet can’t be exactly like any picture we have of the present. It can’t be exactly like any record of the past.

Many science fiction stories have been written about people colonizing the planet Mars and going on from there into the Asteroid Belt. It’s reasonable enough to imagine that once people are living on Mars, it won’t be hard to get a little farther out. What we know of the Belt tells us that it’s made up of thousands of chunks of rock and metal. Some are little more than boulders; some are as large as houses; some are little worlds in themselves. The large ones are usually called planetoids. Ceres, for example, is 480 miles in diameter.

The Belt lies between Mars and Jupiter, and the majority of the asteroids are in one orbit around the sun, following approximately the path a planet would if it were there. Few of them are round, and we'll probably find some very peculiar shapes among them. Over three thousand have been discovered to date, and the chances are that there are many more which we haven't seen from Earth.

In most of the stories that have been written about mining on the asteroids so far, authors have decided that life out there will be much like frontier days on Earth. They’ve pictured Mars in a state of civilization like that of the Middle West of 1848 (as compared to the East Coast), and the asteroids like California in the Gold Rush days. They describe people living in “boom towns’' and working out on the “frontier.”

This is one point of view, but perhaps the difference will be so great that the similarities won't seem very important.

Let's look into some of these differences; let’s picture, first of all, the differences between someone’s going to California in 1848, and someone’s going to Mars in the near future.

If you weighed 100 pounds when you started out for California, back in ’48 or '49, the chances are you'd lose some weight getting there. But if you took 100 pounds of baggage, and arrived with all of it, that baggage would still weigh 100 pounds. If you start out for Mars, at the same weight, and with the same amount of baggage, that 100 pounds will be only 38 pounds when you arrive. Everything on Mars weighs 38 per cent of what it weighs on Earth.

What effect will this have on the way you live? Well, for one thing, you'll have to learn to move slowly and carefully. If you do not—zoom!—up you go into the air. You’ll find that you can lift a great deal more, and work harder without feeling tired. But you can still strain yourself. After awhile, you’ll learn not to hurry. Life will move along at a relaxed, easy pace—very different from the hurried manner we all live today.

If you went over the mountains on your trip to California, you would find that the air became thinner. You might have a bit of trouble breathing until you became used to it.

But on Mars, if you just stepped out of the ship without special equipment, you’d find you could not breathe at all. You’ve heard about deep-sea fish which explode when they are brought up to the surface of the water. Where those fish live the pressure is so great that a man (or even a submarine) would be crushed—but they are used to it. We are used to living under about 15 pounds air pressure bearing down on each square inch of us. Now the difference between air pressure on Earth and on Mars isn’t so great that we’d explode like a deep-sea fish. But it’s large enough so that we couldn’t breathe.

The air on Mars is thin, too, and extremely dry; you’d injure your lungs seriously with the first breath if you managed to get a breath in. Before we can breathe Mars air, we have to have pressure and moisture. That means you’d have to go around in some land of air helmet.

Our newcomer to California would find that there were many natural sources of food, water, and shelter in most parts of the state. He could learn to get along, "living off the land,” once he was away from towns.

But the best knowledge of Mars we have, so far, shows that there are no natural food sources. There is little or no water handy, and most likely nothing which could be used to build shelter. Science has made it possible to do wonders in converting materials into products we can use. We can make plants grow in all kinds of deserts and get water out of unlikely-looking places. There is probably plant life on Mars.

Our adventurer will have to bring his food with him, and all manner of equipment for growing and converting what he needs.

Now you can begin to get an idea of what kind of society we are likely to have when Mars is colonized. It will have to be a society of highly skilled technicians of all kinds. Everyone must contribute; everyone must work with everyone else. There can be no place for a “lone wolf" or glory-grabber.

In ’48 you didn’t have to pass any tests or get a permit to go to California. All you needed was the ability and courage to get there. But the people who go to Mars will have to pass many different kinds of tests, and one of them will be the ability to get along with other people. Co-operation, thrift (not in money, but in avoiding waste of all kinds), and consideration for the other man will become a part of their way of life.

Such a society has already grown up on Mars in the present story. Alan Clay, and his son, Peter, have lived all their lives in this new world. We would find it astonishing. We’d be amazed at the scientific progress in just about every field that has to do with food, clothing, shelter, health, communication, and so on. But at the same time we would marvel at the lack of comfort, and the absence of many things which we take for granted here.

Alan and Peter have never breathed “fresh air”— although the air they do breathe is purer than most of us have known. Peter has never seen a tree, a brook, a sunset, or a bird. He has never eaten meat or fish. He's never seen a book such as you are reading. He can read—but his “books” are spools of tape, or films run th

rough projectors. He probably knows much more about television than we do, although he’s never known it as a means of entertainment. He’s seen movies, but they have been “educational” and “documentary” films.

He’s studied history and art, but Martian art is on the “practical” side. He learned music as a child, can play an instrument, and often composes music. He goes to concerts—music sessions, he calls them—but not to sit and listen. He takes his violin with him and plays in a group with others. They may play an arrangement of something Peter wrote for violin and cello — his father’s instrument — or compositions by someone else in the group. Or it may be arrangements of Haydn, Mozart, or some other famous composer of the past.

He likes baseball and other sports where you try to outwit or outplay the other fellow, but not to knock him out or injure him.

He judges people he meets by the way they act after he’s met them. He would never think of forming an opinion of a man beforehand.

We find him on Ceres, one of the large asteroids. It's much smaller and colder than Mars, though; there’s far less light; and the gravity is very low. It’s as new

to him as settling on another continent, where few other people already live, would be to us. And here, some bits of "history” do begin to take shape in ways that are familiar to us—though not as much so to him.

If this book should be read by anyone in the future, who is actually mining out in the Asteroid Belt, I’m sure that—for all the care and thought that went into it—he’ll find my picture amusing. But I hope that such a reader will find Peter and the other men and women interesting, and even believable people!

R.W.L.

Chapter 1 Claim Jumpers

Somewhere in the darkness, a metallic-sounding voice was repeating: “20-47 Clay! 20-47 Clay! 20-47 Clay!” over and over, as if nothing would ever stop it. Peter Clay seemed to be floating out of the depths of sleep, as the voice cut into whatever dream it had interrupted. Yes, he was floating, but something bound him too. He could feel the tightness of straps around him, and it seemed that this was all that kept him from drifting away into the darkness.

Then he heard sounds that became familiar as sleep vanished. He heard his father slowly loosening straps that held the elder Clay, as they did Peter. He listened, and heard Alan Clay's feet slide into weighted shoes as he arose slowly from his bunk and shuffled over to the communicator. There was a short snap as Clay switched on the lights before plugging in the two-way circuit, and all the haziness vanished from Peters mind.

It wasn’t a dream. This was Cerestown, the asteroid-miners’ domed city on the surface of the 480-mile planetoid that swung in its orbit in the Asteroid Belt. The mysterious Belt lay between Peter’s home world, Mars, and mighty Jupiter, where no human being had landed. This was the frontier he’d heard of since childhood and dreamed about visiting—the outpost of human civilization which had come from Luna, Earth’s moon, and Earth itself in his grandfather’s time to settle on Mars.

Peter smiled as he remembered that his presence here was no visit, but an adult’s choice of occupation. Most kids weren’t cleared for such a choice until they were eighteen, Earth style, and Peter was only a little over seventeen, by the old reckoning. You had to pass tests, no matter what your age. Peter had come through, saying he wanted to join his father in Cerestown and work with him in his lead mine.

When I go back home to vote, he thought, I’ll vote against the New Reckoning Bill. There was a strong movement to throw out Earth-style reckoning for people’s ages where birthdays were celebrated every twelve months—and go by the Martian calendar— which had twenty-four months in the year, twice as many as Earth. Why, he thought, that would make me only eight and a half. Who wants to be a child so long?

Slowly he loosened the straps around him, and let one leg out of the bed as his toes felt for a magnetized shoe. You had to be careful on Ceres, or you’d go sailing into the air and slam into something. Peter smiled as his fingers crept to a bump on his head. That was a reminder of the last time he’d forgotten. He’d shot up to the ceiling of the small room one morning, when he tried to jump out of bed as he would have on Mars. There was hardly any gravity at all on Ceres, and unless you were wearing special shoes you'd sail up into the air at the slightest sudden motion.

He heard his father say, “20-47 Marlene,” and knew that the speaker on the other end would be either Glen or Barbara Abend, neighbors on Asteroid 20-47. They worked a copper mine there. Having friends on one of the many rocks in the sky that made up the asteroids was something to be grateful for—even if Glen Abend did see a claim jumper in every shadow, as Alan Clay said. Well, you had to take some precautions, of course. Voices on a communicator sounded pretty much alike, except for very high or low pitches, so people who knew each other had their own private signals. This week, when either the Clays or the Abends got a call starting out “20-47,” the answer had to be “20-47 Marlene.” The next time they got together, they’d decide on a new countersignal— to guard against deception, Abend insisted. Clay thought it was a bit overdone, but Peter like the idea.

Pete shuffled over to the food cabinet, took out a can of dehydrated soup, switched on the electric stove and started to add the necessary water. It was a new thing to have all the water you wanted, and more. He still felt uneasy when he wasted more than a few drops.

A voice came from the communicator. “Have you seen Glen, Alan?”

Clay shot a glance in Pete's direction, and frowned slightly, his blue eyes tightening under his ruddy forehead. “No—I sort of expected to see him at the music session last night. Hasn't he come in yet?”

Pete looked into the mirror, and decided it wouldn't be long before his skin was as tanned as that of his father. He wouldn't look as striking as the elder Clay, whose blue eyes made such a contrast with his white hair and his skin. Pete was now well over six feet, and still growing. A six-foot-tall Martian was just average. Well anyway, they wouldn't be calling him “Whitey” much longer. All the lights here contained ultraviolet, as they did on Mars. Ceres-dwellers needed the ultraviolet even more than Mars-dwellers, for this planetoid received far less sunlight. When they stopped calling you “Whitey,” that meant you looked like one of them.

“He’s two days overdue already,” Barbara’s voice was saying, “and I've asked all the officials, but they don t know anything. If I could get out myself . . . Barbara had been laid up for over a week, after a blaster-cap exploded too soon, slamming her against the rocketside. “Glen has been talking so strange, and not his usual gloom; I think maybe something might be wrong.”

“Didn’t say what, did he?”

“No—you know Glen. He talks by the day when he’s worrying about something just in his head. But let real trouble come up and you can’t get a word out of him until he’s positive. He has to argue it all out with himself first. Alan, have you or Petey ever heard of ‘Ama?’ Clay turned around. “Pete, have you heard of any new claims? Any new asteroids?”

Peter snapped off the stove and picked up the two heated cans of soup, placing suction tubes into the openings. “Nope, I haven’t. Golly, partner, they sure dream up strange names for them, don’t they?”

“Yeah. ... No, Barb, the name doesn’t mean anything to us. Look, we’re going out to work pretty soon. We’ll look in at your mine. Maybe he’s just working overtime and has forgotten to call.”

"Maybe. I'll be ready to go out myself in a week or so. Sorry to bother you."

“No trouble; we’ll let you know as soon as we find out anything.” Clay cut the connection, and turned to breakfast. “Well, Pete, my trick for cooking starts tomorrow, then you can sit around and get served. Don’t rightly see that there’s anything to worry about unless Glen’s had an accident. Our mine and Glen’s put together wouldn’t be worth a claim-jumper’s time. We’ll make the first one who comes along a present of it next year—if it pans out the way it’s going now. That’ll give us enough for a grubstake; then I’ll show you what the

rough life is really like, fellow—prospecting.” He grinned. “You’ve been living in sheer comfort, in case you didn’t know it.”

It was always “night” outside the dome, or so close to it that you might as well call it night. Ceres rotated slowly, but the Cerean “day” was but a matter of a few hours, and the difference was one between a faint glow and inky blackness. You had to have a spacesuit once you left domed Cerestown—a suit with lights, air supply, heating unit, and a communicator.

The Clays shuffled along the icy surface soundlessly, their lights illuminating a small area about them as they headed toward the rocket field which lay a half-mile away. Pete had tried to hurry it up by taking big jumps the first time—only to find that his father was well ahead of him when he landed with a thump that jarred him from head to foot.

‘‘Lesson number one, partner,” Clay had said, grinning, “Loss of weight doesn’t mean loss of mass or inertia, and it’s mighty slow sailing.”

They felt a faint vibration in their feet, and turned slowly to wave at an approaching tractor. Miners’ cargoes were hauled from the field into the dome for assay, refining, and sale by the public transportation department. The tractor chuffed up to them, and a deep, friendly voice sounded in their suit receivers. “Going out to the field?”

It was a question that needed no answer. Without Waiting for a reply, the driver continued, "Climb aboard and save your strength.”

Clay and Pete scrambled up to a resting place as the tractor moved on. “Hi, Whitey,” the suited driver said to Pete, “getting a good look, eh? Well, some folks say it gets dull after a while, but don’t you believe ’em; there’s always something to see here if you watch the sky.” He pointed up to a faint flash in the distance above them. “There goes an iceman.”

Peter stared, but couldn’t make out anything in what seemed like millions of pin-point lights in the sky over his head and beyond the short horizon. “You’ll get the hang of it after a while,” the driver said. “Took me some time, too, but I caught a glint of ice on that fellow’s ship. Can’t see the ship, of course; it’s buried inside a chunk the size of a mountain.... First miners here were icemen; people didn’t get to looking for metals until later. Now all the icemen work for Mar-supply, so no one else bothers.”

Mystery of the Third Mine

Mystery of the Third Mine